The Paradox of Innovation: Origins, Adoption, and the Traits of Change-Makers

The world, in its astonishing complexity and diversity, is a magnificent cradle for the birth and dissemination of innovation. However, innovation, particularly in the modern era, is not distributed evenly across all cultures, countries, and religious groups. A close examination reveals that only a small segment of the global population is responsible for the majority of innovations, leaving one to ponder why this is so and what mechanisms are at play.

Since the end of the Second World War, the United States and Western Europe have emerged as powerhouses of innovation. Even within these regions, it is only specific segments of society that birth novel ideas that eventually transform into tangible, influential innovations. This uneven distribution raises pertinent questions about the ability and willingness of different societies to foster innovation.

For decades, countless regions, some of which are economically developed, have seemingly not contributed any noteworthy innovation. Certain countries, particularly those under specific religious ideologies, seem to lack the propensity for novel thinking, with their innovation droughts lasting not just years but centuries. This trend begs the question: what makes these societies apparently innovation-averse?

There is a range of potential factors at play here, including socio-economic conditions, educational paradigms, cultural perspectives, religious orthodoxy, and political climates. For instance, strict adherence to traditional religious dogmas might inhibit the creative thinking necessary for innovation. Equally, a society’s economic situation could also influence its innovative capacity.

Ironically, while certain societies may discourage or fail to generate innovation due to conflicting orthodox religious views or socio-economic challenges, they often end up adopting and benefiting from the very innovations they initially resisted. This apparent hypocrisy creates a paradoxical relationship between the origin and adoption of innovations.

Let’s take a look at some examples that underscore this paradox of innovation origin and adoption.The history of science is replete with examples that reflect this paradox of origin and adoption of innovation. One notable instance is the acceptance of the Germ Theory of Disease.

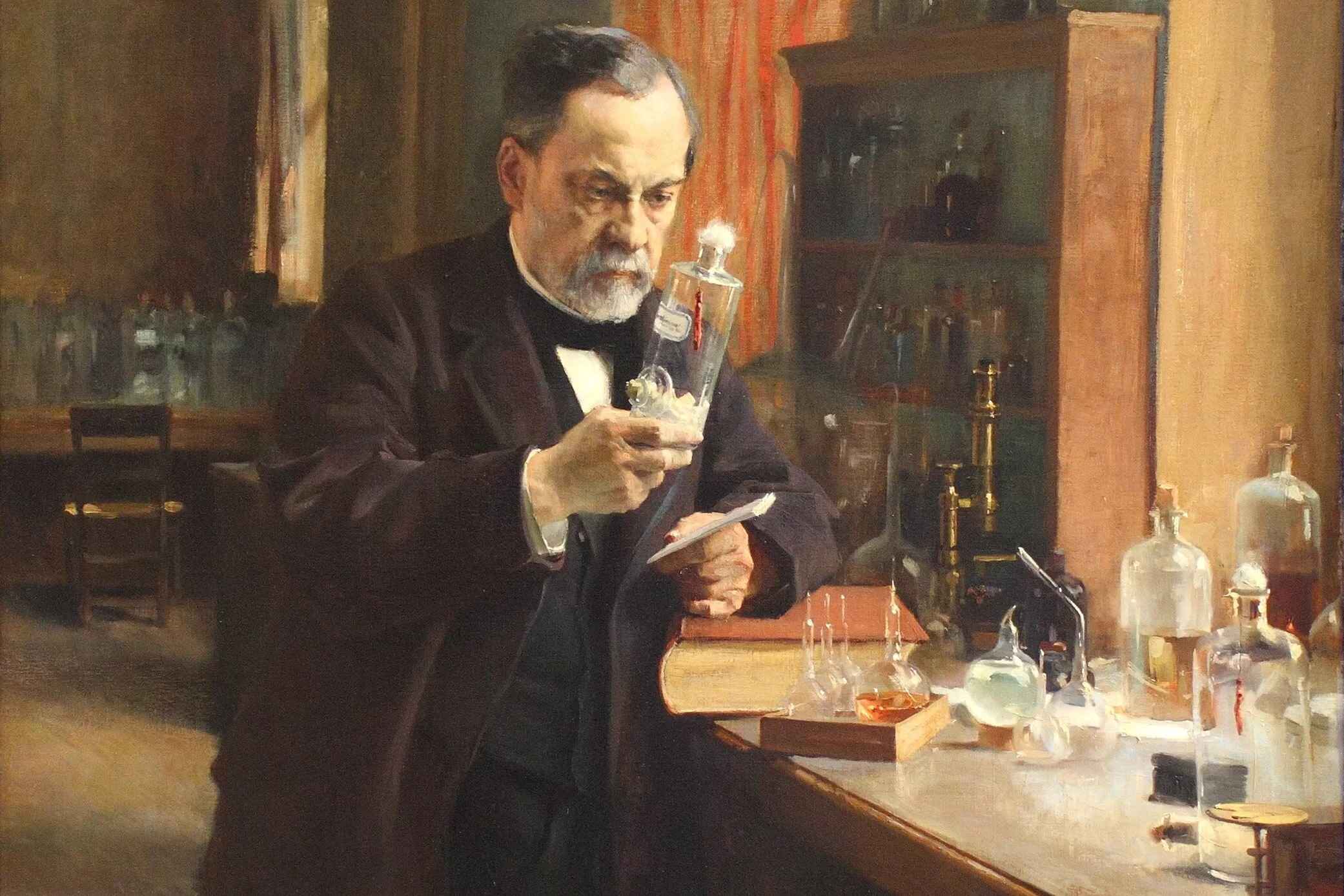

The Germ Theory of Disease, which asserts that specific microorganisms cause specific diseases, was predominantly developed in Western Europe during the late 19th century by scientists like Louis Pasteur of France and Robert Koch of Germany. This theory marked a significant departure from the prevailing miasma theory of disease, which attributed illnesses to “bad air” or a polluted environment.

However, the acceptance of the germ theory was not instantaneous, even in the West. Many physicians and scientists, entrenched in the miasma theory and other older ideas about disease causation, initially resisted this new approach. The shift in understanding disease was not merely scientific but required a change in deeply entrenched social and cultural perspectives on health and disease.

Moreover, in many non-western societies, the germ theory directly challenged traditional or religious understandings of disease. For instance, in some cultures, illness was often attributed to supernatural causes or moral failings. Consequently, acceptance of the germ theory in these societies was slow and fraught with resistance.

Yet, as the evidence for germ theory became overwhelming and its practical implications for treatment (antibiotics) and prevention (vaccines and sanitation) became clear, it was gradually accepted worldwide. Today, germ theory is a foundational principle in medicine and public health, widely accepted across cultural and religious boundaries.

This example again underscores the dynamic tension between the origins of innovation and its eventual global adoption, influenced by a complex interplay of scientific evidence, cultural beliefs, and societal readiness for change.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution:

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection provides a remarkable illustration of this dynamic.

Developed in the 19th century, Darwin’s theory challenged the prevailing views of the time, particularly the religiously-rooted belief in the immutability of species and the notion of a literal interpretation of creation. Originating in Western Europe, his ideas were met with vehement opposition from religious institutions and some segments of society that saw them as a direct challenge to their deeply held beliefs.

The resistance to Darwin’s ideas was not confined to Europe. In societies around the world where religious or traditional views held sway, his theories were often regarded as heretical or subversive. For example, in many societies with a strong belief in creationism, the idea that humans and other species shared common ancestors was seen as deeply offensive.

However, as the scientific evidence supporting Darwin’s theory accumulated over the years and the explanatory power of his ideas became evident, more and more societies began to accept the theory of evolution, even if it challenged their traditional beliefs. This process was often gradual and not without resistance. It took decades, if not longer, for Darwin’s theory to gain widespread acceptance in some societies, and in others, the acceptance is still a contentious issue.

Today, Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is a cornerstone of modern biology and has been adopted worldwide as the central explanation for the diversity of life on Earth. This acceptance has occurred despite its initial rejection in many societies, reinforcing the complex dynamics between the origins of an idea and its eventual widespread acceptance.

Genetically Modified Organisms:

Another example comes from the realm of biotechnology, particularly the advancements in Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs). Pioneered largely by scientists in the United States and Western Europe, GMOs promised to revolutionize the agricultural sector by improving crop yields and resilience. However, numerous societies, particularly in parts of Africa and Asia, initially resisted these innovations due to cultural, religious, and sometimes unfounded health concerns. Despite this, as the global population continued to grow and the need to secure food supply heightened, many of these societies eventually adopted GMOs to benefit from their enhanced agricultural productivity.

Mobile Technology:

A forth example lies in the widespread adoption of mobile technology. This innovation, again primarily developed in the U.S. and Western Europe, faced initial resistance in various parts of the world due to cultural and religious concerns, fears of societal disruption, and economic constraints. For instance, in certain conservative societies, there was a belief that mobile phones could lead to moral decay by facilitating unsupervised communication among young people. Despite this, the enormous utility of mobile technology in enhancing communication, supporting economic activity, and providing access to information eventually led to its widespread adoption globally.

Internet:

A fifth example is the widespread adoption of the internet, a major innovation of the 20th century that was largely developed in the United States. Many societies that initially resisted or showed minimal involvement in the creation of the digital realm are now active participants, reaping the immense benefits the internet offers.

These examples reflect the intriguing dynamics between the origin and adoption of innovation. The global acceptance of an innovation often follows a convoluted path, punctuated by resistance, negotiation, and ultimately, capitulation in the face of undeniable benefits.

Key Characteristics of Innovators:

Innovators and the societies that foster them typically exhibit a variety of key characteristics that contribute to their ability to generate novel ideas and transformative innovations:

- Curiosity: Innovators often have an insatiable curiosity about the world around them. They ask questions, seek answers, and are always ready to explore the unknown.

- Open-mindedness: Those who drive innovation are generally open to new ideas and experiences. They are often willing to challenge the status quo and conventional wisdom, and are open to changing their minds in the face of new evidence.

- Critical thinking: Innovators are typically able to analyze information critically, discern patterns, make connections, and solve problems in novel ways. They are not easily swayed by popular opinion and are able to think independently.

- Resilience: The path to innovation is fraught with failure. Innovators are characterized by their resilience and their ability to persist in the face of setbacks. They view failures as opportunities to learn and improve.

- Risk-taking: Innovation requires a willingness to take risks. Innovators often step out of their comfort zones and are not afraid to venture into uncharted territories.

- Collaboration: Despite the popular image of the lone genius, most innovation is the product of collaborative efforts. Innovators are typically good at working with others, valuing diversity of thought, and leveraging collective intelligence.

- Vision: Innovators often have a vision of what the future could look like. They are driven by the desire to create that future, and they have the ability to inspire others to join them on that journey.

- Lifelong learning: Innovators are committed to continual learning and skill development. They stay abreast of advancements in their fields and are often multidisciplinary in their interests.

- Absence of Mental Blocks: Successful innovators typically do not let mental blocks hinder their creative process. They strive to overcome cognitive biases, preconceived notions, or any form of fixed mindset that may stifle creativity or prevent them from exploring new perspectives and possibilities. They cultivate a growth mindset that views challenges as opportunities for learning and growth.

- Compartmentalization of Religious Ideologies: While innovators can come from diverse religious backgrounds, they often possess the ability to compartmentalize their religious beliefs when engaged in innovative pursuits. They can distinguish between the spiritual and empirical domains, ensuring that religious ideologies do not hinder the rational and evidence-based thinking essential for innovation. This doesn’t mean they disregard or disrespect their religious beliefs, but they understand the different applications and implications of science and faith.

These characteristics highlight the intellectual flexibility and resilience often necessary for successful innovation. It’s a delicate balancing act, maintaining personal beliefs while engaging in free-thinking, evidence-based exploration, but it’s a common trait among those who pioneer transformative changes.

In the context of societies, the presence of strong educational systems, supportive governmental policies, access to resources, and a culture that encourages questioning, risk-taking, and tolerance for failure can significantly contribute to the production of innovation.

It’s important to note, however, that while these traits increase the likelihood of producing novel ideas, innovation is a complex process and can emerge in a variety of contexts and from individuals with diverse characteristics.

In conclusion, understanding why innovation predominantly occurs in small segments of the global population requires deep exploration into the socio-economic, cultural, religious, and political underpinnings of societies. Recognizing the paradox between innovation’s origins and its global adoption is crucial in appreciating how societies navigate the tides of change while grappling with their entrenched beliefs and ideologies. The tale of innovation, thus, is not just about technological advancements but also a story of societal evolution and the paradoxical dynamics of acceptance and resistance.